What happened to Dutch pirates who tried to loot Tiruchendur Temple in 1648

by Prof. K.A. Nilakanta Sastri, Published in Kalaimagal 1939 p. 412

Photos © 2021 courtesy of Śrī Subrahmanya Swami Devasthanam, Tiruchendur. Reproduction by permission only.

Tirumalai, the greatest of the Madura Nayaks, ruled over the South of India between 1623-1659 A.D. The Portuguese were the earliest European traders to land at Cochin, and Tirumalai eager to have foreign trade relations concluded a treaty with them in 1639 A.D.

The pearl fishery which employed the Paravas of the coast brought them enormous wealth. The pearls were the wealth of the Pandyas, and now that of the Portuguese.

Notwithstanding they were not enterprising enough, and Tirumalai was in consequence inclined more towards the progressive and prosperous Dutch who had large settlements along the Malabar, Ceylon and Chola mandala coast with factories and forts.

The Portuguese were the earliest European traders to land at Cochin, and Tirumalai (1623-1659 A.D.), the greatest of the Madura Nayaks, was eager to have foreign trade relations concluded a treaty with them in 1639 A.D. The pearl fishery which employed the Paravas of the coast brought them enormous wealth. The pearls were now the wealth of the Portuguese.

Accordingly a treaty with the Dutch was concluded in 1646 by terms of which they were allowed to build a fort at Kayal-pattanam. This brought them into conflict with the Portuguese. They seized a Dutch boat laden with goods and drove the Dutch out of their fort and destroyed it.

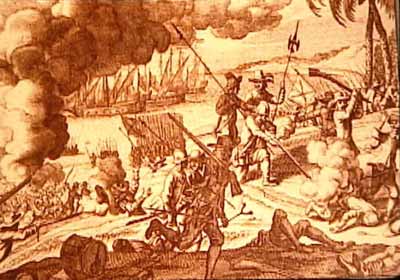

The Dutch sought the aid of their Governor at headquarters in Ceylon. He came over to the mainland in ten boats, landed at Manappar, seized the Portuguese Church at Virarampattanam, occupied the Temple at Tiruchendur and fortified the latter with guns.

The people were sorely distressed and they appealed to Tirumalai Nayak. The Nayak sent word to the Dutch to vacate the temple and re-imburse their loss at Kayalpattinam. The request was unheeded. The Dutch nevertheless marched on Tuticorin, ravaged the country all around it, and demanded 40,000 rials as a ransom to quit the place. The amount was also pressed for payment but only a small amount could be got together.

In the meanwhile the people at Tiruchendur gathered a force consisting of four elephants, 50 to 60 horses, and 500 to 600 men to oust the Dutch out of the temple. The attempt was unsuccessful with the loss of 50 men of the Nayak forces. The people were utterly helpless and sorely tried.

In 1648 the Dutch left the country taking with them all the temple idols, and demanding an enhanced ransom of 100,000 rials. The Nayak and his agent Vadamalai Pillayyan sent an embassy of four men to the Dutch in to demand the return of the temple idols. The Dutch Governor referred the demand to Dutch Government at Batavia, who directed the return of the idols to the temple at Tiruchendur, accepting however whatever amount they were offered.

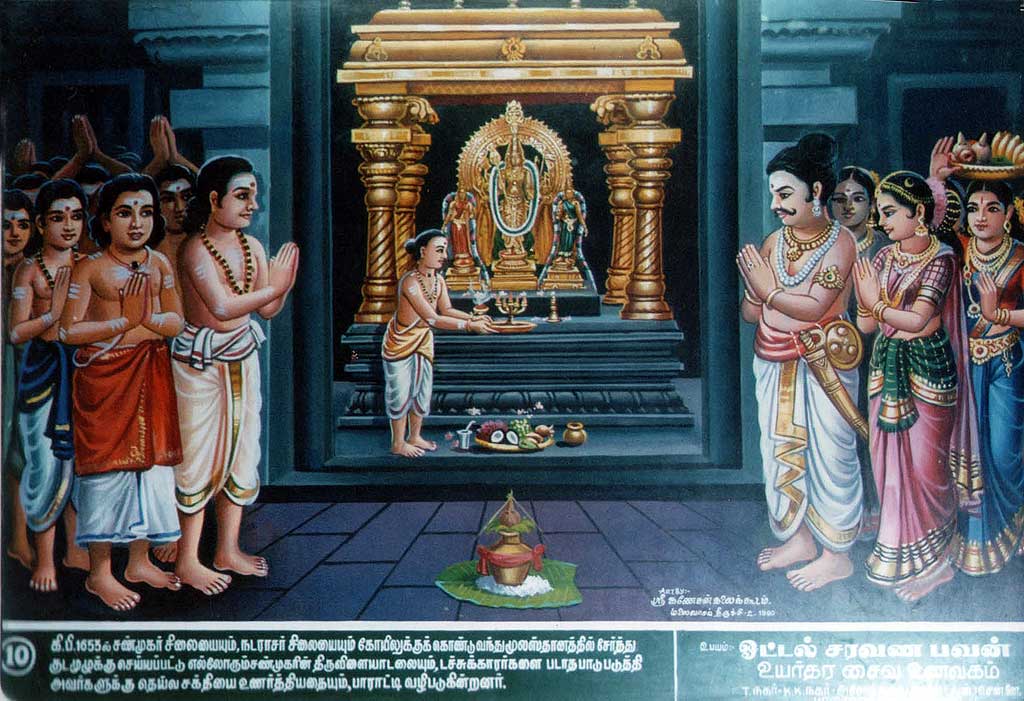

Accordingly the idols were brought back to Tiruchendur in January 1651 and re-installed at the temple after consecration. And the inscription of Vadamalai-appa Pillayyan mentions this incident as in kolam 869.

As against this historical background of the event, the popular tradition goes that the Dutch as marauding pirates plundered the country, carried away the temple bronzes and threw them into the sea to escape a divine retribution, and it was given to Vadamalaip Pillayyan to rescue them from the ocean’s keeping. History and tradition, though different, have abundant morals to the discerning and the devout!

The Dutch adventure of 1648-53

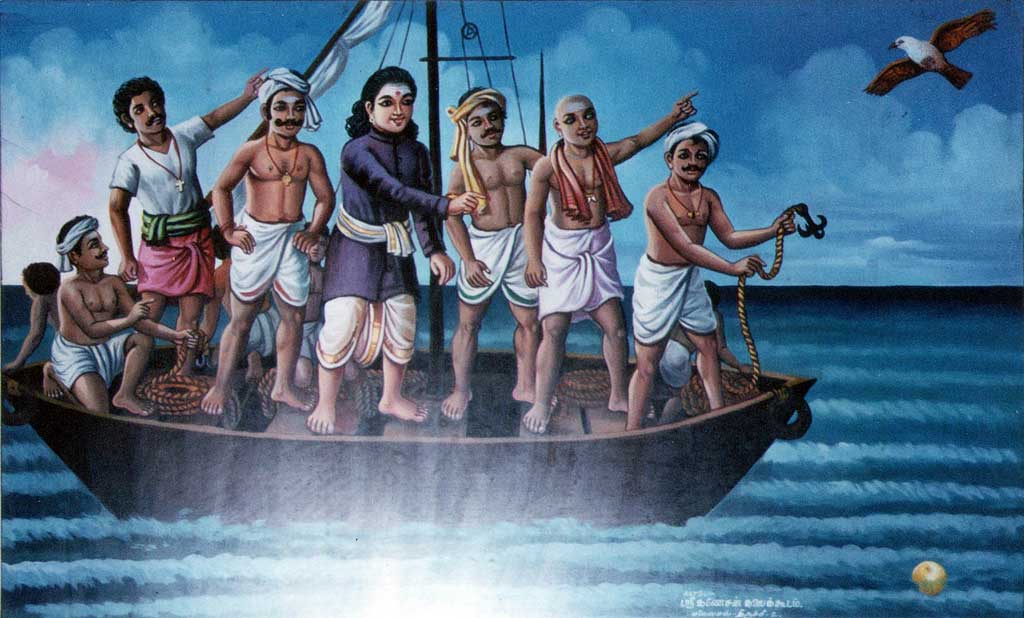

A familiar local tradition runs to the effect that about 1648 AD, a race of seafaring men, identified later as Dutch, descended upon Tiruchendur and carried away the idol Shanmukhar and Śiva Natarajar, thinking that they were made of gold. Their attempt at melting it proving futile, they tried to carry them away by sea. But the sea suddenly grew boisterous, and rocked the ship violently, so the sailors threw the idols into the sea.

The loss of the idols was discovered and duly communicated to Vadamalaiyappa Pillaiyyan, the local administrator of the Nayakkan ruler at Tirunelveli. A great devotee that he was, Pillaiyyan was sorely affected and knew not what to do. He ordered for a similar idol to be made in panchaloka (an amalgam of ‘five metals’). As the duplicate one was ready, and was on its way to Tiruchendur to be installed, in 1653 Vadamalaiappa Pillaiyyan had a dream.

Acting to the advice conveyed to him by the God, he put out to sea and following the instructions that the idol was to be found at the spot whereon a lime fruit would be found floating, and the place marked by the circling overhead of a kite, the bird of Vishnu.

Vadamalaiappa Pillaiyyan recovered the original idol and reinstalled it in the temple in the year 1653. The replacement idol was then consecrated in the shrine of Tiruppirantîsvarar alias Venku Patcha Kovil situated east of Palamcottah (known as Murugan Kurichi).

Vadamalaiappa was greatly struck by the Lord’s grace in giving him this great relief, in memory of which he erected a mantapa at Tiruchendur in his name and endowed it largely for the performance of a Kattalai abhishekam and pujas for Subrahmaniam on the seventh days of Masi and Avani festivals. An inscription at the mantapa relates the incidents referred to.

Among many others, kirtanas composed by Venri Malaik Kavirayar, are sung at this mantapa at the time when Shanmukhar is brought here for Ubaya Mandagappadi on the seventh day of the Masi and Avani festivals. The poem relates the incidents and their rejoicings at the Lord being got back again. “Vadamalai Venba” is another poetic panegyric on Vadamalaiappa Pillaiyyan.

M. Rennel, the French author of A Description, Historical and Geographical, of India (published in Berlin, 1785), gives a picture of the temple, which, he says, he got from a soldier in the service of the Dutch Company. He relates an incident which offers a reasonable explanation of the Tiruchendur tradition. “In a descent made by the Dutch off the Coast in 1648,” he says, “the Dutch halted in the temple and on leaving did their best to destroy it by fire and by a heavy bombardment. But they only partially succeeded and the tower defied all their efforts.” Possibly the capture of the idol was one of their achievements.

As a matter of fact M. Rennel calls the place Tutucutin, but from the picture and an accompanying sketch-map it is clear that Tiruchendur was meant. The Dutch were incessantly at war with the Portuguese on the coast.

From an article by Prof. K. A. Nilakanta Sastri published in Kalaimagal 1939 xvi p. 412

reproduced in Somasundaram Pillai, pp. 46-7.